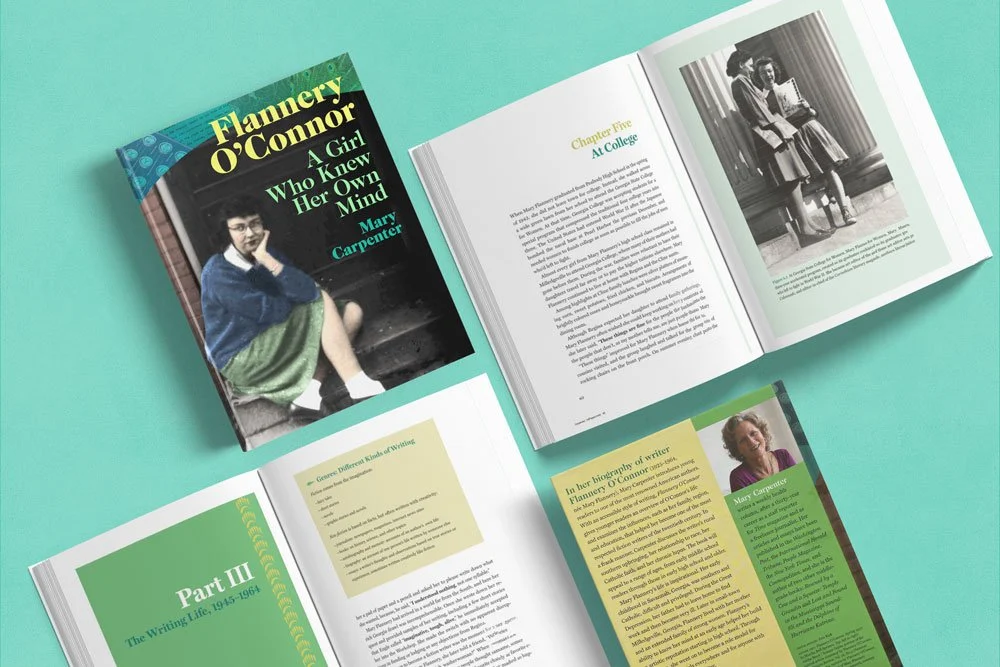

Flannery o’Connor

A girl who knew her own mind

By Mary Carpenter

Prologue

Knowing her own mind and sticking to her guns gave Mary Flannery a voice that was strong and distinctive when she began writing fiction. Writing under the name Flannery O'Connor, she worked hard every day. She wrote her stories for years if necessary, to get them exactly the way she wanted them to be told, or, as she put it, until she enjoyed reading them and no longer got bored.

At crucial points in her career, she risked angering two very influential people: the publisher who had already paid money in advance for her first novel and a prominent literary critic in the middle of a live TV interview. She refused to do what these men asked because she was so sure of what she wanted to say and how she wanted to say it.

Table of Contents

-

Chapter One: Staring and Listening

Chapter Two: Chickens

Chapter 3: Catholic and Southern

-

Chapter Four: Cartooning

Chapter Five: At College

-

Chapter Six: Becoming a Writer

Chapter Seven: Return to the South

CHAPTER 1:

Young Mary Flannery stood for hours at her parents’ bedroom window. She had on the clunky supportive shoes, which she hated, so her mother wouldn’t pester her to wear them. And she wore her “leave-me-alone” look, as she called it, to keep anyone from bothering her. She wanted to stand there, to look and to listen. She had no idea that spending hours paying close attention to her world was the best preparation possible for becoming a writer.

Chapter 3:

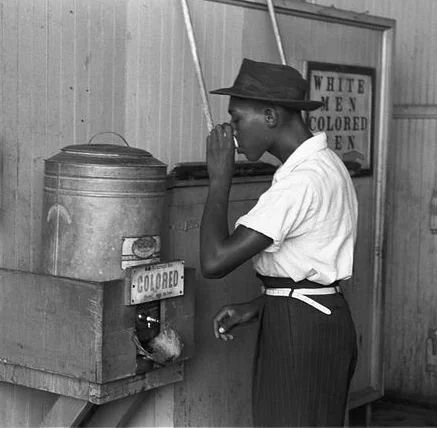

Mary Flannery also lived during the time of “Jim Crow” laws that required Black people to use separate water fountains and sit in the back of public buses…The look and feel of the Old South may have persisted longer in Savannah than elsewhere, because the city was one of the few in the South left undamaged after the Civil War… Mary Flannery disliked the sanitized and dishonest stories of the Old South told by sentimental books and movies of the time.

Epilogue:

Flannery O’Connor continued speaking eloquently to her readers long after her death in the middle of the twentieth century. She never lost the peculiar, almost rude, and clearly southern voice of the teenager on a double date who said, “My dad-gum foot’s gone to sleep.” Flannery’s voice came from a lifetime of listening and watching the people around her and from her quirky interests, especially in birds, starting with the amusing chickens and ducks of childhood and ending with the vain peacocks of Andalusia.